A new project at The Australian National University (ANU) shifts from the Australian history told from our colonial beginnings to one told by Aboriginal people, with stories that connect their recent past to the ancient history of their traditional lands.

Under the direction of the ANU Research Centre for Deep History, Professor Ann McGrath and mapping consultant Kim Mahood worked with Aboriginal Elders associated with the Lake Mungo region to record their family stories.

“The Elders of the Mutthi Mutthi, Nyaampa and Barkintji spoke about how their families were forced to move from mission to mission,” Professor McGrath says.

“A lot of the children were stolen. They worked all over the sheep stations in the region. They often saw ancient footprints and things when they were working. They were drovers, they worked on railways.”

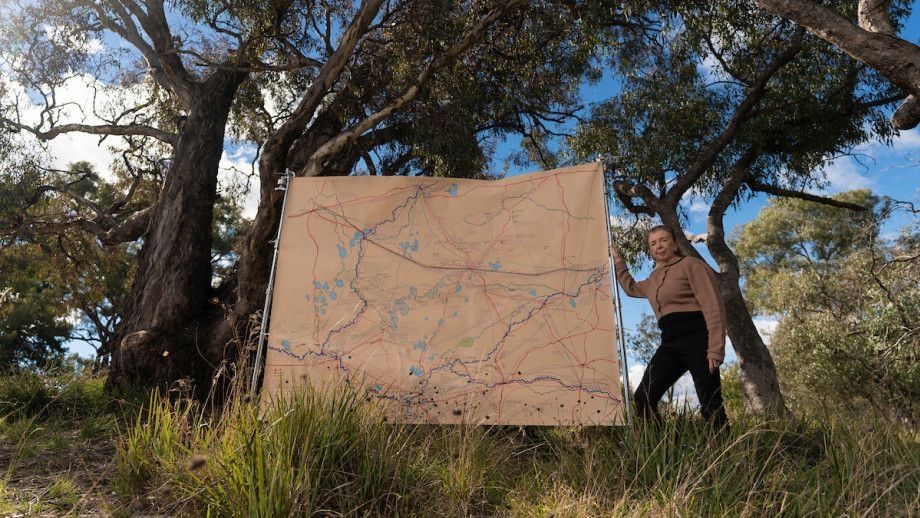

Professor McGrath thought a good way for Aboriginal people to be able to tell these stories would be on a map that shows these movements on their traditional lands.

“These maps are often called cultural maps, but this is essentially a history map. This map offers a strong visual history, going back several generations. Some people also mention bunyip stories and ancient stories that wouldn’t really have a date,” she says.

As a historian, Professor McGrath was interested in how to switch away from the colonial narrative of Australia’s history, and tell the stories of the country’s First Nations people.

“Aboriginal people tell the story of a very important woman who’d been buried 42,000 years ago in Mungo, which I thought was amazing,” she says.

“That’s a biography, that’s a human being that we can relate to. I met lots of amazing Indigenous elders and young people and Aboriginal people who were Discovery Rangers at the National Park. They were proud to tell their stories of this ancient woman.”

Academics typically write books or journal articles, which are standards of academic outputs, but Professor McGrath “knew these Aboriginal people weren’t particularly interested in our books at all”.

“They were, however, proud to tell their stories of this ancient woman. We made a film about it called Message from Mungo, which came out in 2015. They’re able to speak in their own voice, and they’re able to directly tell you what they see is important in history.”

Fast-forward to today’s project, which captures their more recent history and ongoing connection with traditional lands through the retelling of ancient stories.

“Aboriginal people have a very different relationship with the deep past. They talk about Lady Mungo like she’s an aunty who died yesterday,” Professor McGrath says.

“Aboriginal Elders asked, ‘Why are you only interested in our ancient past? What about our more recent past? We’ve got our own biographies, with our grandmothers, our great grandmothers. These stories need to be heard too.”

The map tells the stories of their families’ own connection to Country, which itself is a deep history of deep connection to lands of ancient association.

“Even though these people were forced by the Government to keep moving from one mission or government reserve to the next, they still stayed very close to Country. They’re still staying there today in these little towns.”

Bernadette Pappin, a Mutthi Mutthi woman, says the stories on the cultural map comes from “the mouths of Indigenous people and not non-Indigenous people”.

“We are telling our story; everybody’s got a story, got a connection to this land here that we are talking about,” Ms Pappin says.

“It shows the storyline of our people and where we belong and where we come from, and other people having an understanding of where we are, and we still are today.”

Patricia Johnson, a Paakintji Elder, says the map helps her heal.

“I believe it will help all my people too, the same way how I feel,” she says.

The project will have a handover ceremony, with a proposed traveling exhibition through each of the communities where Aboriginal people shared their stories. A digital interactive version of the map, with historic photographs shared by participants, will be made available on the Research Centre for Deep History website. Project leaders are in talks with the National Library of Australia about plans to digitise the map so that it is available worldwide.