The crisis of COVID-19 may be a rupture in history but it is one that offers a historic portal into a new era. The impact of the pandemic is affecting the entire world in myriad ways, with enduring legacies we cannot yet know. It is a crisis of time that might open up new ways of thinking, working and being.

One thing is certain – the coronavirus pathogen has become an actor in history, leading to all kinds of ramifications. As author Arundhati Roy reminds us: “unlike the flow of capital, this virus seeks proliferation, not profit, and has, therefore, inadvertently, to some extent, reversed the direction of the flow.” It is highlighting inequalities, and through its global horror and tragedy, it is both separating and uniting people.

For academics, we have seen endless cancellations of historical gatherings, alongside many invitations to zoom webinars and meetings. We may be looking more inwards too, reconnecting with our writerly selves. This pandemic is forcing us to see time differently – and the home differently, including our planetary home and health. Corona connects us with the commonalities of past plagues and outbreaks, where social distancing was long used as a prophylactic.

Historians of deep history might also begin to think carefully about humans as hominids, as part of ‘nature’, with bodies hosting many different kinds of microbial life invisible to the naked eye. Some involve co-dependencies going back into deep time. Domestication of animals has often been portrayed as a key development in social evolution – if not the beginnings of the societies imagined as superior ‘civilizations’. Humans then become the ‘tamers of nature’. Yet, along with the benefits of animal domestication came powerful pathogens that have caused a range of pandemics, including smallpox and whooping cough, many of which are still with us today.

The Corona crisis reminds us of how humanity cannot control death, and yet humanity has been keen to do so, and to mark people’s passing, throughout every time we know in history. Ritual burials and cremations go back at least 40,000 years in Australia alone, for example those of Lady Mungo and Mungo Man – modern homo-sapiens like us. They were also seen as ‘scientific evidence’ that our university colleagues held for far too long, returning most of those in their laboratories only in the past few years. Their extraction from their country, and their graves, impacted the mental health of Indigenous custodians, who suffered great anxiety about the fate of their ancestors.

Elders presiding over the return of Mungo Man, Lake Mungo NSW, 17 November 2017. Photo by Ann McGrath.

Corona prompts reflection, too, about the terrible shock suffered by the Eora people of the Sydney region when they were hit by a widespread smallpox epidemic in 1789, the year after the British convicts arrived. The mass illnesses and huge number of deaths were shocking, devastating. What would they have made of this crisis, this terrible plague that wiped out babies and elders alike? What kind of psychic adjustments and realignments had to be made to cope with such a thing, which took place at the same time as the ongoing crisis caused by invading lawbreakers who took over their lands and fishing grounds? Their deeply held knowledge of medicinal herbs and techniques, and all the controls they had developed to ensure the world was a healthy place had to be readjusted in some way in order for them to survive. The physical, intellectual and spiritual challenges were enormous. Adjusted explanatory frameworks, with rich stories and songs that expressed ways of framing the past, present and future, started to evolve.

This morning (at 5am, due to the time difference), I attended a webinar held by Harvard’s History Department, ‘What History Teaches us about Pandemics’, which included the Chair of the Initiative for the Science of the Human Past (SoHP) Mike McCormick, who has long been a generous supporter of our program’s work, and one of our Collaborating Scholars, Joyce Chaplin.

“What History Teaches Us About Pandemics.” The Public Face of History Series of the Harvard History Department.

Another participant, historian Erez Manela, reminded us of how in the 1960s, science was seen to reign supreme; after all, this was era of the moon landing – and of an internationally successful program that wiped out smallpox. He showed us a document on which the first signature was that of the wonderful Australian National University microbiologist and virologist a Frank Fenner. I recall how honoured I was when Professor Fenner, who led the initiative to eradicate smallpox via a vaccine, introduced himself after attending one of my very first public presentations on deep history. (Here was another example of interconnected historical worlds.)

Screenshot from “What History Teaches Us About Pandemics.” The Public Face of History Series of the Harvard History Department. 21 April 2020.

In her presentation, historian Joyce Chaplin characterized Europeans themselves as the ‘pestilence’. They brought terrible diseases to the Americas, to Australia and New Zealand and the islands of the Pacific – measles, colds, cholera, smallpox and venereal diseases to name only several. These European pestilences, intentional weaponizing of disease or historical accidents, they devastated Indigenous nations. She reminded us that, nonetheless, they were fundamental to the foundation of the United States, aiding and abetting the takeover of native lands. The same was true of other New World nations like Australia.

It is impossible to imagine the challenge that this huge tragedy, this terrible imperial assault on their people, posed for the Eora. Large numbers of outsiders had taken over their lands and their fishing areas without invitation or permission, and were now preventing them from accessing their food supplies and their pharmacopoeia. Aboriginal people at Sydney Cove had long established knowledges, informed by land-based ontologies of health and disease. We do not know if their experiences through their deep past had necessitated the development of isolation practices to prevent contagion. More research is needed on this topic, and Neil Brougham, one of the program’s PhD students, is researching the deep history of smallpox as we speak.

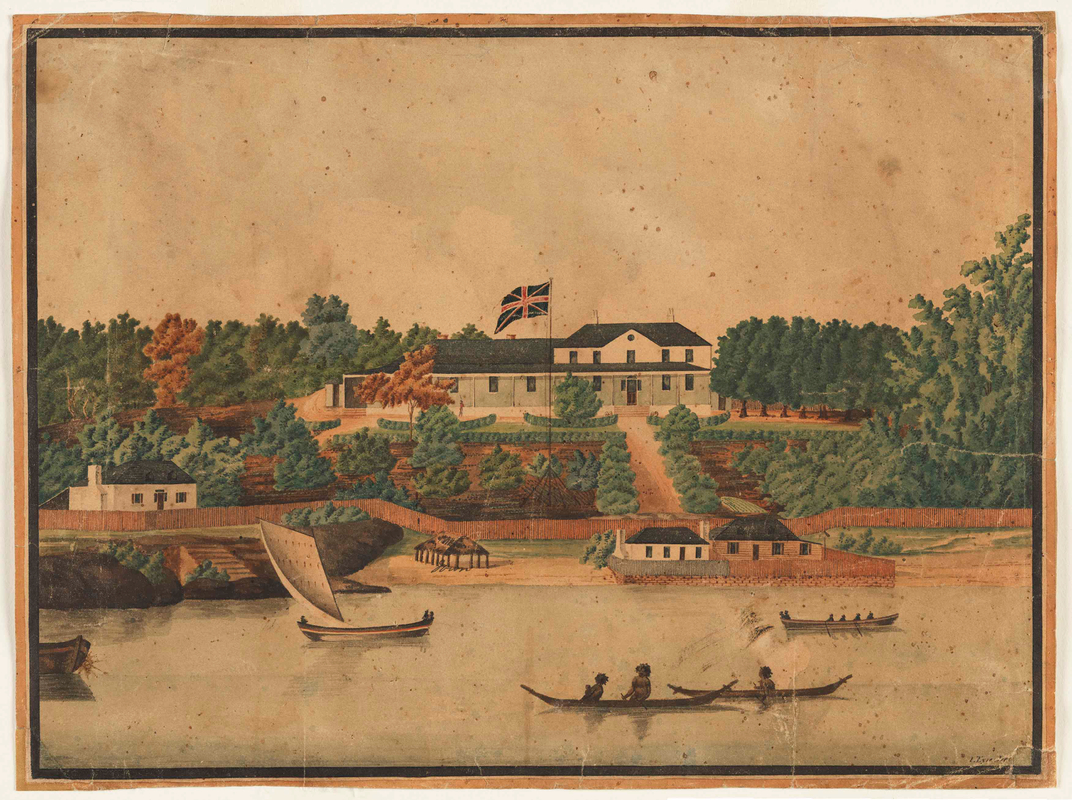

Some of my earlier research provided an intimate glimpse into the last days of one of the many individuals who died in this pandemic. In 1789, when an elderly Eora man and a child were brought up to Sydney Cove very ill with smallpox, Arabanoo, who then resided at Governor Phillip’s house, looked after them. Arabanoo nursed the ill children and the old man with dedication and tenderness. Known as Manly to the British due to his impressive masculine physique and demeanour, Arabanoo was one of the people kidnapped by Governor Arthur Phillip’s party. He now remained at his residence, unshackled, perhaps because he was motivated to learn about the newcomers’ culture and to conduct intelligence and diplomacy for his people.

Many more seriously ill Eora people soon arrived seeking help around Sydney Cove and the Governor’s house. Nearly everyone else who arrived soon after died. However, the children attended by Arabanoo recovered. Tragically, Arabanoo caught the virus, and within six days, he died from it. Arthur Phillip arranged for Arabanoo to be buried in his private garden at the Governor’s residence. It was akin to a state funeral in the sense that it was presided over by the Governor. Arabanoo had taught the British that Aboriginal people were humane and caring of old and young; they were not the ‘savages’ that Europeans liked to think. As John Hunter, second in charge of the First Fleet, commented: ‘Every person in the settlement was concerned for the loss of this man.’ The Europeans mourned him, and perhaps people of the present day should do so too.

Novelists and historians alike help us reflect upon how humans respond in times of crisis. Geraldine Brooks’ novel Year of Wonders: A Novel of the Plague propels the reader into another kind of historical moment – one with different belief systems, with a world of different sizes, becoming smaller, but still connected with outside visitors, including traders that bring in materials from distant lands. I recommend this wonderful novel of humanity, motherhood, and conflicts of religious and medical belief.

In 2020, the time of Corona, Arundhati Roy reminds us that:

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.

Coronavirus has been a wake-up call about the value of science in a ‘post-truth’ world, and it also highlights humanity’s ever-encroaching impacts upon animals and the wider living world around us and inside us. If Corona is to provide a portal, we might hope that it is one through which we might refresh our approaches to modernity’s long impact on the environment and to climate change.

Finally, two of our good colleagues have this to say about history and pandemics:

Gunlog Fur, scholar of the Delaware, US, and the Saami, Scandanavia Linnaeus University, Sweden:

In my own work on indigenous history, epidemics have been an ever-present and unavoidable theme, and one that has challenged communities fundamentally and recurringly to rethink relationships, leadership, ceremonies and material practices.

Manuela Picq, Amherst University and University of Equador:

The pandemic has brought a deep transformation in meaning and it will likely be a different world and humanity once we re-emerge on the other side of it. It will be what it will be, when it will be. The timeframes of the past are gone. Forever I hope.

For historians, this pandemic will raise many new questions about how we might address the deep past. I sincerely hope that this global crisis gives us insight into the best paths for the future, informed by fruitful directions for unravelling humanity’s deep past. And I do hope that you may join us on this journey. Indeed, we need some hope right now.