-

Boomerangs out of the past

Research Centre Collaborating Scholars Duncan Wright and Dave Johnson have been doing amazing work. Read all about their discovery of six boomerangs of great academic, community, and cultural significance.

-

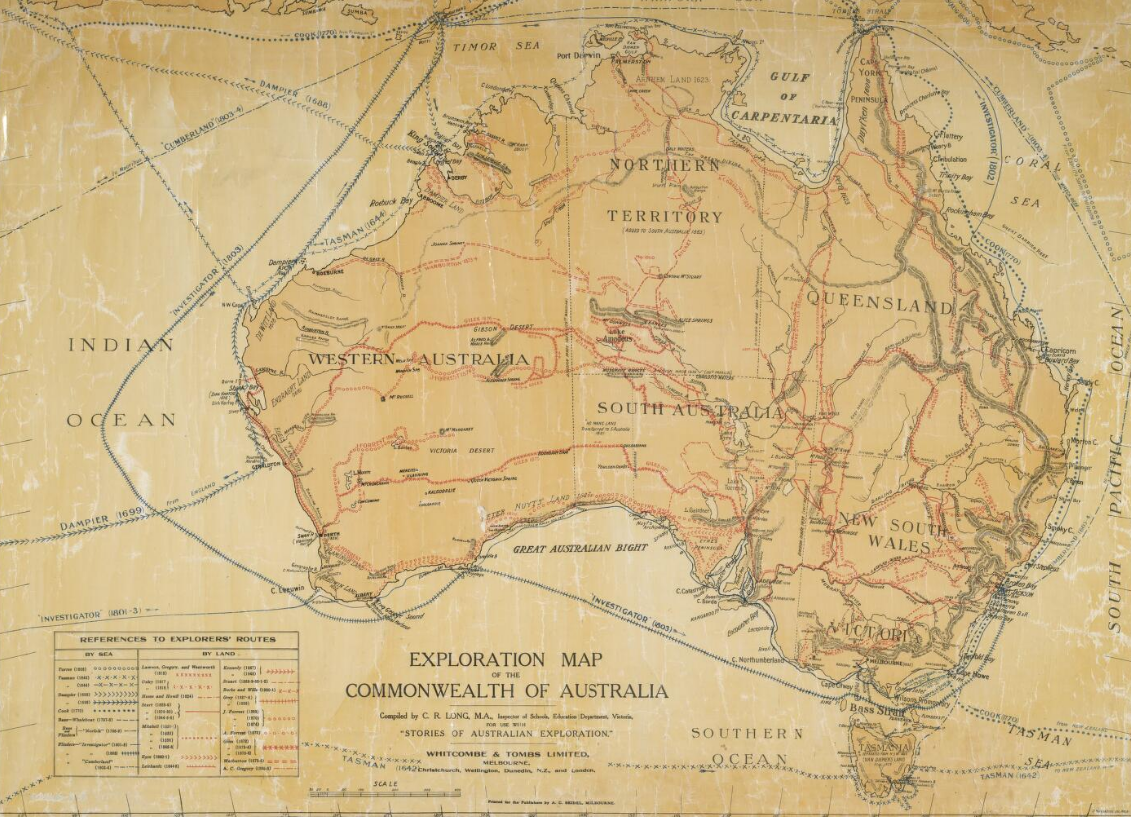

Monumental discovery narratives and deep history

The Research Centre Director, Ann McGrath, has written a new article on deep history. Published in the latest edition of the Humanities Australia Journal, it contrasts the destruction of the Indigenous heritage site of Juukan Gorge with the police protection awarded the statue of James Cook in Hyde Park. She argues that the nationalist narratives of discovery obstruct a clear view of the deep past. In order to advance the study of deep time, she argues that the history discipline requires reconceptualization and the development of new tools. She concludes that “to prevent discovery’s monumental features continuing to block the view of deep time, historians need to appreciate indigenous interpretations of the deep past, and work with Indigenous leaders to ensure future histories of nation align with Indigenous sovereignty and inform reparative justice. To do so, the discipline’s parameters must be open to radical change”.

-

Aboriginal Workers: a 1995 special issue of Labour History revisited in 2020

The 1995 Aboriginal Workers Special Issue of Labour History edited by Ann McGrath, Kay Saunders, and Jackie Huggins was recently relaunched, with a new introduction, and a blog interview from Liverpool University Press (LUP) which you can read at their website.

-

Reviewing Song Spirals

The Deep History team have been inspired by the recent publication Song Spirals: Sharing Women’s Wisdom of Country through Songlines, written by the Gay’wu Group of Women, and were pleased to see it win the non-fiction category in the Prime Minister’s Literary Awards.

The ANU’s Stories Reading Group hosted a lively discussion about the book and Ann McGrath and Julie Rickwood each wrote reviews of the book, now published on-line and which you can read here:

Ann McGrath’s review: https://aboriginalhistory.org.au/book-reviews-pre-publication/songspirals/

Julie Rickwood’s review: https://openjournals.library.sydney.edu.au/index.php/JASAL/article/view/14836

Ann suggested that it is “a poetic exploration of Indigenous women’s ontologies” while Julie stated that it is “a unique invitation into Aboriginal women’s traditional cultural practices”.

Both were captivated by Song Spirals and highly recommend it.

-

The role of sound in the creation of place and identities

My interdisciplinary practice-based PhD is primarily concerned with sound’s role in the creation of place and identities, and I explore some of these themes within the context of a silent expeditionary film shot in North Western Australia in the 1920s.

In 2019 I spent time field recording in the Kimberley region where my attention was taken by the ancient landscape and how something of it might be captured in sound.

In sound acquisition we have numerous tools at our disposal. For example, geophones can be used to capture the seismic activity of the earth, contact microphones capture structure-borne sound and hydrophones can capture underwater sound. I find the acoustic properties of spaces particularly evocative, and so a high-quality condenser microphone that renders airborne sound is what I chose to deploy.

Old Broome Jetty Site (Groyne Area). Photograph by Rob Hardcastle. I was struck by what I heard when lowering the microphone into cavities in rock formations. The resulting recordings gave me an immediate sense of a connection to something ancient, something relatively unchanged – a sonic bridge to a different time. The resonant nature of sound lends itself to this bridging with the past, and when combined with country this can become particularly evocative, as Ruth Gilbert of the Wiradjuri people observes, “I feel most connected to my country when I stand still and listen. I can hear the voices of my people, my ancestors.”

Coulomb Point. Photograph by Rob Hardcastle. In addition to the more creative experiments above, it would be interesting to capture the acoustics of geographical spaces that we understand to be relatively unchanged since the first humans passed through them. Caves would be an obvious candidate, particularly as we often have evidence of a past human presence in the form of cave art, remains and artefacts, but also open plains where the topography, flora and fauna might have seen little change in over 40,000 years. Resulting recordings might eventually serve as acoustic artefacts for a landscape changing through human intervention, such as those imposed by climate change or the destruction of significant sites like Juukan Gorge.

One purpose of ANU’s Research Centre for Deep History is to “formulate imaginative ways of conceptualising the past”. With this in mind, I would like to return to the region with more time, and perhaps as part of an interdisciplinary team to explore some of these concepts further.

-

Director’s Blog – Shamrock Aborigines, NAIDOC, and beyond

On 10th November, I had the pleasure of attending a NAIDOC event hosted at the Irish Embassy in Canberra by the Ambassador of Ireland, HE Breandán Ó Caollaí and Ms Carmel Callan. This has become an annual event, with an invited gathering of leading representatives from the Canberra Aboriginal Community and a special recognition of the Ngunnawal people and key ACT Aboriginal representative organisations, including Indigenous educational bodies and businesses. John Paul Janke, the Co-Chair of the NAIDOC Committee 2020, spoke about NAIDOC. Beforehand, John Paul and I had the chance to discuss the importance of songlines and deep history stories, which he noted was a fundamental theme to this year’s NAIDOC week, ‘Always Was, Always Will Be’. He explained that this had been selected as particularly pertinent given that 2020 is the anniversary of James Cook’s Landing. We agreed that deep Indigenous histories, once more widely understood, will transform the dominant discovery narratives of Australia.

The event centred around a screening of the award-winning film – An Dubh ina Gheal-Assimilation to which I’d had the honour to contribute. I was invited to provide a short talk in response.

The film was a beautiful, albeit harrowing experience, as it told the truth about Aboriginal history in Australia. Echoing some of the themes explored in my article “Shamrock Aborigines”, it explored Aboriginal-Irish relationships, the myths and realities. But it went far beyond that, with quality research and interviews conducted in Melbourne, western Victoria and the Northern Territory. Throughout the film, which featured excellent archival footage, historians and activists including Gary Foley, Kev Carmody, and Henry Reynolds shared their views.

One of the most moving aspects of the film was hearing about the intimate relationships between the Byrnes family of Tipperary station; tragically, under Commonwealth of Australia policy, children of mixed descent (renamed as Brock after child removal) were torn away from their mothers and placed in institutions run by Catholics, including many Irish Catholic nuns. The children suffered, being brought up without their mother’s love, and enduring punishments for speaking in their own languages. It brought back memories of my research for my Doctoral thesis, which in fact featured several discussions about the Byrnes’ recognition of Indigenous ownership of the land that they occupied.

An Dubh ina Gheal- Assimilation also celebrated Indigenous rights struggles. As you’ve no doubt gathered, it did not romanticise the relationship between the Irish and the Aborigines in any way – quite the opposite – the Irish were colonists too, and the film-makers embraced their own responsibility as colonizers, and how they benefited as such. At the same time, there was a sense of a profound connection between the Irish and the Aboriginal people, both having been oppressed and dispossessed at the hands of the English, and still suffering historical legacies, including the destruction of their languages.

The film is enhanced by the poetry of Louis de Paor, who is also the film’s presenter. In searing lines, in a poem entitled Didjeridu, he explores how the Irish, as white Australians, were also brutal colonizers. It was read by Carmel Callan in both Irish and English.

Responding to the Film at Irish Embassy NAIDOC week event, 10 November 2020. Last week I also attended the Annual Symposium of the CABAH group, with whom I’m an Associate Investigator. Updates about the latest scientific research and findings of their regional Flagships were most informative.

Finally, I participated in a video for a Conference being held in Brazil, convened by Juliana S. Machado and her graduate students and professors Gonzalez Marcelo and Roseline Mezacasa. It was the second Global History Symposium: Voices from the South. We have so much in common with these history scholars who are undertaking important collaborative work with a number of Indigenous peoples across Brazil. At Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina I learnt that the Indigenous cohort is quite significant, and like us, they are working to expand the idea of what history might be beyond the text, and in their case, the larger story of Indigenous people’s histories including those that took place prior to the fifteenth century.

-

Oceanic histories: how seas shaped Australia’s past

How do oceans make histories? Or how do we make histories from oceans? These were questions posed in a recent webinar hosted by the ANU Research Centre for Deep History in conjunction with the Centre for Environmental History, convened by Laura Rademaker and Ruth Morgan. How, participants were asked, have seas shaped Australia’s deep history? We were provided with two engagingly different answers by Lynette Russell and Patrick Nunn, each speaking from a distinctly interdisciplinary position.

These are, perhaps, ontological questions, calling positionalities into question. Damon Salesa has observed that the vast Pacific Ocean, as a named, known, and narrativised place, has its origin in European mapping. To identify this origin is not, of course, to suggest that Islanders were unaware of the ocean, but rather to take seriously the proposition that they experienced maritime places differently to those concerned with mapping empires and globes. The Pacific Ocean, once it was named and experienced as such, rubbed up against but did not dislodge those enduring ‘native seas’. More recently, Islanders have re-possessed and Indigenised the Pacific itself. It has become, in Epeli Hau’ofa’s phrase, a ‘sea of islands’, connecting the Pacific with ‘native seas’ in what we might understand as a decolonising move. Places of history—whether oceans, seas, islands, super-continents, or nations—are emergent in ways that depend on where we approach them from.

Speaking at the webinar, Lynette Russell reminded us of Chief Brody’s quip, in Jaws (1975), that ‘it’s only an island if you look at it from the water’. For Russell, questions of knowledge and perspective are central. How, she asked, is the ocean seen from the land, and vice versa? Insisting on understanding land and sea in relation, on what Alison Bashford has elsewhere termed terraqueous histories, the ocean emerges as a space of unceasing churn, bringing human and more-than-human beings together and apart in new configurations. It can be a space through which people move and a place where they dwell; oceans can be homes, whether temporarily or permanently. An ocean, then, makes new encounters possible, becoming a flowing site of meetings across cultures and languages that generate new ways of being and belonging at and across the seas.

These stories of encounter introduce possibilities of change by, in part, bringing together history and culture while holding onto what makes peoples distinct. These are moving histories, carried along by historical currents that break on shorelines. Greg Dening had tried, in his distinctively transdisciplinary fashion, to write history ‘from both sides of the beach’. The beach was, in his imagination, a threshold over which people met in what were often mutually transformative encounters. As Russell told us, thinking the moving beach as the historical threshold of Australia, as the space from and on which Aboriginal people have met outsiders, helps us to re-frame a deep history of Australia as one not of isolation but of encounter. She provided us with a glimpse of her exciting new Laureate Project, Global Encounters & First Nations Peoples, which in part will explore some of the ways a history of encounter might centre Indigenous experiences and knowledge of others.

The ocean itself is an object of knowledge, and Patrick Nunn took us through some of his research on Indigenous memories of the sea that have been, he argues, passed on through millennia. Surveying the Australian coastline, Nunn identified 27 distinct groups of drowning stories, each of which speaks of water encroaching from the sea, covering the land and never receding. These, he told us using a method familiar to readers of his popular 2018 work The Edge of Memory, can be described as Indigenous Australian memories of post-glacial sea-level rise.

In 1939 or 1940, a Yaraldi man named Karloan told anthropologist Ronald Berndt a story of Ngurunderi, a ‘creative hero’ of ancestral times. Nunn drew our attention to one part of Berndt’s re-telling of Karloan’s story, in which Ngurunderi pursued his two wives until finding them walking from Tjirbuk (Blowhole Creek) to what is now Kangaroo Island. When they reached what is now the centre of the Backstairs Passage, Ngurunderi called the waters to fall upon them. The rushing waters both drove them further south and transformed them into Meralang (The Pages islands), and remained in place, separating Kangaroo Island from the mainland. This part of the story, Nunn argues, is a container for the memory of rising sea levels some 10,080 to 10,950 years ago.

This is one way, as Ruth Morgan put it in her response, of thinking though connection and change over time. And it prompts reconsiderations of how we have and how we might continue to relate to Indigenous historical knowledge, whether of the seas or otherwise. Is that knowledge a resource for answering questions posed elsewhere, by reference to other epistemologies? Or, as Russell suggested, is this the moment to turn to that knowledge in order to ask new questions, from new perspectives?

-

Inscriptions of Nature: a new book by Pratik Chakrabarti

One of the Research Centre’s Collaborating scholars, Pratik Chakrabarti, has published a new book, Inscriptions of Nature: Geology and the Naturalization of Antiquity. A culmination of a research project funded by Leverhulme Trust (UK) entitled An Antique Land; Geology, Philology and the Making of the Indian Subcontinent, 1830-1920, the book seeks to fill an important gap in the scholarship of deep time. It presents a new political history of deep time as a product of European colonialism. It shows that deep history represents a deep Western engagement with nature, which in essence is an intensive, and in some respects absolute, knowledge of nature. This approach provided Western epistemology with deep access to people’s lives, their genealogies and their natural resources.

Pratik notes that there are robust traditions of deep history in the Global South, with eclectic engagements with aboriginality, myths and deep time. These have, however, remained outside mainstream histories of geology and geohistory, which continue to focus on European or ‘northern’ intellectual traditions.

This book engages with these two scholarships to write a layered and integrated ‘New Deep History’.

There are two book launch events, on 4 and 11 December, both at 4pm UK time (which is a challenge for Australian readers). Full details are available via Eventbrite:

-

Oceanic histories: how seas shaped Australia’s past

The Deep History and Science in Conversation Series created two excellent webinars, one on Pandemics, the other on The Anthropocene. If you missed them, both can be viewed via our YouTube channel (link below).

Since then, a new collaborative opportunity was recently created with the appointment of Dr Ruth Morgan to the Centre for Environmental History – the Deep conversations: history, environment, science series. This partnership aims to bring together scholars from diverse disciplines to discuss questions of history, science and the environment, and how they shed light on the global challenges we face today.

We’re now delighted to announce the inaugural webinar: Oceanic histories. On our blue planet, oceans have long shaped human histories. Generations have crossed the seas, fished their depths, and navigated their currents, encountering new peoples and places on the waves and on the shores. In this Deep Conversation, we reflect on just how oceans have shaped deep human pasts and how we can recover ocean histories from the deep.

Time and date

12:00-1:30 PM, Thursday 29 OctoberSpeakers

Professor Lynette Russell, Kathleen Fitzpatrick Laureate, Monash University

Professor Patrick Nunn, University of the Sunshine CoastDiscussant: Dr Ruth Morgan, Australian National University

Chair: Dr Laura Rademaker, Australian National University -

Archaeology and history on Groote Eylandt

Research Centre for Deep History visiting fellow Professor Annie Clarke presented her seminar on the Groote Eylandt Archaeology Repatriation Project to the School of History on 14 October. Having conducted extensive archaeological research in partnership with Anindilyakwa community-members in the 1990s, Annie returned in 2018 to repatriate archaeological material as well photographs of the research where she met me. I was also returning historical materials and publications related to Groote Eylandt at this time. The archaeological material is now housed on Groote Eylandt. During this latest visit, Annie employed community co-researchers to continue work on the repatriated samples which had not yet been fully analysed.

This work is an example of ‘slow’ practice in archaeology. It has become an intergenerational project with daughters of the old man who had conducted research in the 1990s now employed to continue the research. Archaeological analysis was conducted on Country rather than on university campuses such that the community’s participation in and ownership of the research could continue.

There are unanticipated cultural benefits of conducting research in this way. Archaeological findings function as mnemonic devices to generate conversations about culture. For example, findings of a diverse range of shell species became a prompt for broader discussions about Indigenous lifeways, cultural changes and knowledge revitalisation. Visiting important rock-art sites with community members enabled people to share old stories of Macassan visits. Likewise, the photographs of family conducting archaeological research in the 1990s became exceptionally valuable. They prompted discussions around memory, history and culture and became an unexpected archive of this more recent history.

Annie’s research practice reveals the riches of slow, community-based research. It presents a challenge to academic practice which might often be focused on fast and tangible outputs and outcomes. An intergenerational and community-based practice, on the other hand, offers exciting and often unexpected cultural benefits to communities as they use research in ways most suited to them.

Taking family members back to old peoples’ camping places. Photo by Annie Clarke 2019.