-

5th May: ‘Pandemics and the Deep Human Past’: Deep History and Science in Conversation

‘Pandemics and the Deep Human Past’ is the first conversation in the Deep History and Science in Conversation Series, a initiative of the Research Centre for Deep History.

This webinar will be conducted via Zoom. Two hours prior to the event, a webinar link will be emailed out to all attendees registered via Eventbrite.

Speakers

- Associate Professor Simon Reid, University of Queensland

- Associate Professor Maja Adamska, The Australian National University

- Associate Professor Justin Denholm, The University of Melbourne

Deep History Discussant

- WK Hancock Professor of History Ann McGrath, The Australian National University

Series Convenors

- Josh Newham, Research Centre for Deep History, The Australian National University

- Miriana Unikowski, Research Centre for Deep History, The Australian National University

For more information contact the convenors: joshua.newham@anu.edu.au or miriana.unikowski@anu.edu.au.

-

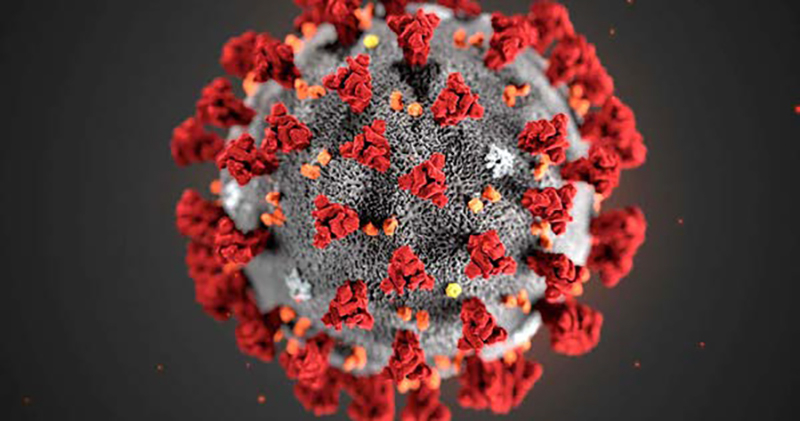

Director’s Blog – Deep History in the Time of Coronavirus

The crisis of COVID-19 may be a rupture in history but it is one that offers a historic portal into a new era. The impact of the pandemic is affecting the entire world in myriad ways, with enduring legacies we cannot yet know. It is a crisis of time that might open up new ways of thinking, working and being.

One thing is certain – the coronavirus pathogen has become an actor in history, leading to all kinds of ramifications. As author Arundhati Roy reminds us: “unlike the flow of capital, this virus seeks proliferation, not profit, and has, therefore, inadvertently, to some extent, reversed the direction of the flow.” It is highlighting inequalities, and through its global horror and tragedy, it is both separating and uniting people.

For academics, we have seen endless cancellations of historical gatherings, alongside many invitations to zoom webinars and meetings. We may be looking more inwards too, reconnecting with our writerly selves. This pandemic is forcing us to see time differently – and the home differently, including our planetary home and health. Corona connects us with the commonalities of past plagues and outbreaks, where social distancing was long used as a prophylactic.

Historians of deep history might also begin to think carefully about humans as hominids, as part of ‘nature’, with bodies hosting many different kinds of microbial life invisible to the naked eye. Some involve co-dependencies going back into deep time. Domestication of animals has often been portrayed as a key development in social evolution – if not the beginnings of the societies imagined as superior ‘civilizations’. Humans then become the ‘tamers of nature’. Yet, along with the benefits of animal domestication came powerful pathogens that have caused a range of pandemics, including smallpox and whooping cough, many of which are still with us today.

The Corona crisis reminds us of how humanity cannot control death, and yet humanity has been keen to do so, and to mark people’s passing, throughout every time we know in history. Ritual burials and cremations go back at least 40,000 years in Australia alone, for example those of Lady Mungo and Mungo Man – modern homo-sapiens like us. They were also seen as ‘scientific evidence’ that our university colleagues held for far too long, returning most of those in their laboratories only in the past few years. Their extraction from their country, and their graves, impacted the mental health of Indigenous custodians, who suffered great anxiety about the fate of their ancestors.

Elders presiding over the return of Mungo Man, Lake Mungo NSW, 17 November 2017. Photo by Ann McGrath.

Corona prompts reflection, too, about the terrible shock suffered by the Eora people of the Sydney region when they were hit by a widespread smallpox epidemic in 1789, the year after the British convicts arrived. The mass illnesses and huge number of deaths were shocking, devastating. What would they have made of this crisis, this terrible plague that wiped out babies and elders alike? What kind of psychic adjustments and realignments had to be made to cope with such a thing, which took place at the same time as the ongoing crisis caused by invading lawbreakers who took over their lands and fishing grounds? Their deeply held knowledge of medicinal herbs and techniques, and all the controls they had developed to ensure the world was a healthy place had to be readjusted in some way in order for them to survive. The physical, intellectual and spiritual challenges were enormous. Adjusted explanatory frameworks, with rich stories and songs that expressed ways of framing the past, present and future, started to evolve.

This morning (at 5am, due to the time difference), I attended a webinar held by Harvard’s History Department, ‘What History Teaches us about Pandemics’, which included the Chair of the Initiative for the Science of the Human Past (SoHP) Mike McCormick, who has long been a generous supporter of our program’s work, and one of our Collaborating Scholars, Joyce Chaplin.

“What History Teaches Us About Pandemics.” The Public Face of History Series of the Harvard History Department.

Another participant, historian Erez Manela, reminded us of how in the 1960s, science was seen to reign supreme; after all, this was era of the moon landing – and of an internationally successful program that wiped out smallpox. He showed us a document on which the first signature was that of the wonderful Australian National University microbiologist and virologist a Frank Fenner. I recall how honoured I was when Professor Fenner, who led the initiative to eradicate smallpox via a vaccine, introduced himself after attending one of my very first public presentations on deep history. (Here was another example of interconnected historical worlds.)

Screenshot from “What History Teaches Us About Pandemics.” The Public Face of History Series of the Harvard History Department. 21 April 2020.

In her presentation, historian Joyce Chaplin characterized Europeans themselves as the ‘pestilence’. They brought terrible diseases to the Americas, to Australia and New Zealand and the islands of the Pacific – measles, colds, cholera, smallpox and venereal diseases to name only several. These European pestilences, intentional weaponizing of disease or historical accidents, they devastated Indigenous nations. She reminded us that, nonetheless, they were fundamental to the foundation of the United States, aiding and abetting the takeover of native lands. The same was true of other New World nations like Australia.

It is impossible to imagine the challenge that this huge tragedy, this terrible imperial assault on their people, posed for the Eora. Large numbers of outsiders had taken over their lands and their fishing areas without invitation or permission, and were now preventing them from accessing their food supplies and their pharmacopoeia. Aboriginal people at Sydney Cove had long established knowledges, informed by land-based ontologies of health and disease. We do not know if their experiences through their deep past had necessitated the development of isolation practices to prevent contagion. More research is needed on this topic, and Neil Brougham, one of the program’s PhD students, is researching the deep history of smallpox as we speak.

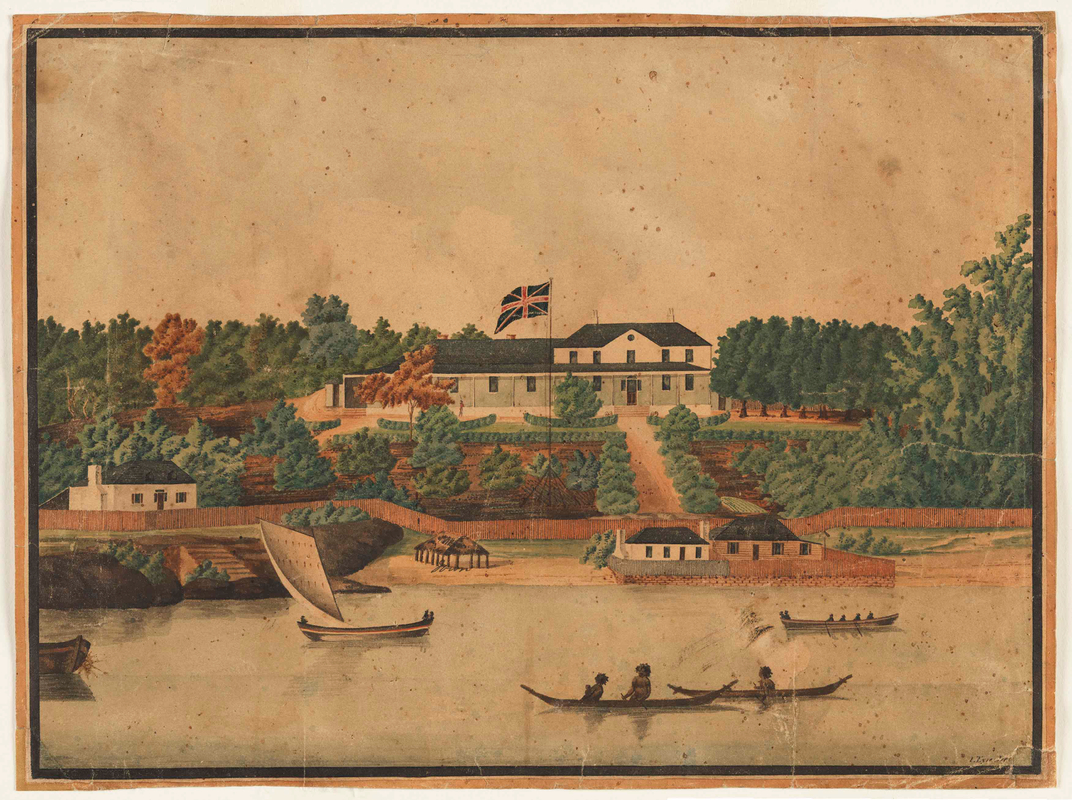

Some of my earlier research provided an intimate glimpse into the last days of one of the many individuals who died in this pandemic. In 1789, when an elderly Eora man and a child were brought up to Sydney Cove very ill with smallpox, Arabanoo, who then resided at Governor Phillip’s house, looked after them. Arabanoo nursed the ill children and the old man with dedication and tenderness. Known as Manly to the British due to his impressive masculine physique and demeanour, Arabanoo was one of the people kidnapped by Governor Arthur Phillip’s party. He now remained at his residence, unshackled, perhaps because he was motivated to learn about the newcomers’ culture and to conduct intelligence and diplomacy for his people.

Many more seriously ill Eora people soon arrived seeking help around Sydney Cove and the Governor’s house. Nearly everyone else who arrived soon after died. However, the children attended by Arabanoo recovered. Tragically, Arabanoo caught the virus, and within six days, he died from it. Arthur Phillip arranged for Arabanoo to be buried in his private garden at the Governor’s residence. It was akin to a state funeral in the sense that it was presided over by the Governor. Arabanoo had taught the British that Aboriginal people were humane and caring of old and young; they were not the ‘savages’ that Europeans liked to think. As John Hunter, second in charge of the First Fleet, commented: ‘Every person in the settlement was concerned for the loss of this man.’ The Europeans mourned him, and perhaps people of the present day should do so too.

Novelists and historians alike help us reflect upon how humans respond in times of crisis. Geraldine Brooks’ novel Year of Wonders: A Novel of the Plague propels the reader into another kind of historical moment – one with different belief systems, with a world of different sizes, becoming smaller, but still connected with outside visitors, including traders that bring in materials from distant lands. I recommend this wonderful novel of humanity, motherhood, and conflicts of religious and medical belief.

In 2020, the time of Corona, Arundhati Roy reminds us that:

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.

Coronavirus has been a wake-up call about the value of science in a ‘post-truth’ world, and it also highlights humanity’s ever-encroaching impacts upon animals and the wider living world around us and inside us. If Corona is to provide a portal, we might hope that it is one through which we might refresh our approaches to modernity’s long impact on the environment and to climate change.

Finally, two of our good colleagues have this to say about history and pandemics:

Gunlog Fur, scholar of the Delaware, US, and the Saami, Scandanavia Linnaeus University, Sweden:

In my own work on indigenous history, epidemics have been an ever-present and unavoidable theme, and one that has challenged communities fundamentally and recurringly to rethink relationships, leadership, ceremonies and material practices.

Manuela Picq, Amherst University and University of Equador:

The pandemic has brought a deep transformation in meaning and it will likely be a different world and humanity once we re-emerge on the other side of it. It will be what it will be, when it will be. The timeframes of the past are gone. Forever I hope.

For historians, this pandemic will raise many new questions about how we might address the deep past. I sincerely hope that this global crisis gives us insight into the best paths for the future, informed by fruitful directions for unravelling humanity’s deep past. And I do hope that you may join us on this journey. Indeed, we need some hope right now.

-

Deep History Reading Group 2020

The Research Centre’s Deep History Reading Group recommenced via Zoom meetups on 17 April.

The Reading Group is chaired by PhD scholar, Josh Newham, and began last year. Previously it was a gathering of ANU scholars interested in Deep History. The current pandemic has prompted an expansion of the group beyond the ANU, including Collaborating Scholars from interstate.

In this fourth meeting since the initiative began, Josh provided a chapter from Steve Webb’s Corridors to Extinction and the Australian Megafauna titled ‘Australia: From Dreamtime to Desert’. In his invitation, Josh said that he found the chapter to be a particularly engaging and enjoyable romp through 4.5 billion years of history and one that somewhat blurred the lines between Big and Deep histories, Environmental History, Archaeology, Palaeontology, Anthropology, Geology and Geography.

The abstract described the chapter as “an overview of the 4.5 billion year evolutionary history and biological development of Australia as a continent. There is particular emphasis on documenting the salient palaeontological discoveries which have occurred in Australia. That includes some of the earliest examples of evolutionary change among the planet’s biota. This chapter also charts Australia’s continental evolution parallel to these events and its development as the driest inhabited continent in the world. Ice Ages and deserts have their introduction here as an indication of what there is to come in later chapters.”

Josh commented that he thought that the abstract didn’t do the chapter justice as it was a wide ranging and erudite read.

Our lively conversation included Josh and Julie from the Centre, Collaborating Scholars Greta Hawes and Linda Barwick, as well as Julie Hotchin from the School of History.

The group commented on the chapter’s expansive coverage, its elegant, crisp and individual style, clear narrative thread connecting the deep past to the present, and on the ways in which the author’s approach centred the landscape as an active character in the narrative.

That said, the chapter certainly received some critique: its lively style was read as both annoying and charming, or both at the same time. Some readers noted a tendency towards a moralistic tone, and most critically, much evidence was not referenced. Rather, Webb simply acknowledged the scholars from whom he had drawn the evidence.

Unfortunately too, the opening of the chapter, which makes reference to Australian Indigenous ontologies and ‘Dreamtime’ was never engaged with again. This salutary reference to Aboriginal culture in the chapter felt somewhat cursory as no Aboriginal perspectives were included in what turned out to be a very scientific narrative of glacial maxims, paleogeography and Darwinian evolution. As these issues and the larger debate around megafaunal extinction feed into ongoing debates around colonisation, genocide, climate change and the anthropocene, the lack of Indigenous perspectives on the deep history of the Australian continent in the chapter was a missed opportunity that may have enhanced it.

The reading group will reconvene mid-May with a new reading by Dennis Byrne entitled ‘Deep Nation: Australia’s Acquisition of an Indigenous Past’. If you are interested in participating please contact joshua.newham@anu.edu.au.

-

Visiting Scholar Bruce Buchan’s latest publication

Associate Professor Bruce Buchan, the Research Centre’s recent visitor, has been published in Arena. A captivating examination of the notion of time in the Anthropocene, Bruce eloquently captures humanity’s relationship with time:

“We humans have always understood ourselves as creatures in time—carriers of meaning from the past, and imaginers of futures pieced together, as a palimpsest, from memories, legacies and echoes. Wrapping us around like a trailing shroud, time tangles about our feet. We humans only ever stumble forwards. Time is our constant companion. Its beat demarcates our shared mortality. It is time that venerates received wisdom. It is time that lacerates us with inherited suffering. Time feeds our future fears as it kindles our cherished dreams.”

He later describes how time reveals itself in the present:

“Time in the Anthropocene is weird. It seems warped, buckled and bent out of shape. The future we forebodingly forecast only yesterday is overborne by even worse predictions today. It is as if the passage of time has been creased and folded back upon itself, tugging the present through and beyond the future, making futures past; it bends our anticipations back into the immediate present and reveals them as decades-long-dead possibilities. In the Anthropocene, projections of the future have no purchase in the present.”

The major question Bruce explores is “What must humanity be or become when we are out of time?” and the journey he takes the reader on to answer that is engaging and compelling. Enjoy the read.

-

Research Centre Activities: Before and during COVID-19

Visiting Scholars:

Professor Annie Clarke arrived for the first half of her visit in early February. During her visit, Annie mentored Research Centre team members and attended the team retreat, including leading a workshop on history and archaeology. Annie provided lively contributions throughout the three days of the retreat. All things going well, Annie will be returning for her second visit in October.

Associate Professor Bruce Buchan was a Visiting Scholar in March. During his brief visit, Bruce presented ‘Failed or Unfinished? On The Fragments of Colonial History in Scotland’s Enlightenment’ at the School of History Seminar. The seminar and follow-up conversations were rivetting. Bruce will be back when circumstances allow.

Both visitors were supported by the Research School of Social Sciences (RSSS) Visiting Scholars Program.

Annual Retreat

The Centre and Laureate program’s Annual Retreat was held at the National Library of Australia from Tuesday 18 until Thursday 20 February. We had a full three day program with a different focus each day:

- Themes, interdisciplinarity and collaborations.

- Review of progress and meeting project deliverables.

- The future, planning of the next three years.

Collaborating Scholars Shirleene Robinson, Mary Anne Jebb, Maria Nugent, Annie Clarke and Duncan Wright joined the team for a morning tea on the Tuesday, followed by a discussion of transdisciplinary opportunities for collaboration.

Highlights:

- National library experts Shirleene Robinson and Mark Piva ran an oral history training workshop.

- RSSS Visitor Annie Clarke led a workshop on archaeology and deep history.

- The review of the project’s outcomes for 2019 showed that we had achieved significant milestones.

- Mike Jones led a workshop on digital humanities and digital history which was followed after lunch by a discussion on data training and the project’s data management plan.

- Tabs Fakier gave us an introductory tour of the Centre website and the team discussed branding and social media.

On the final day, we undertook planning for the next three years of the Centre and Laureate program, with many debates and discussions on theoretical and methodological considerations interwoven throughout.

It was a very productive retreat which highlighted the high quality work being undertaken and planned by all members of the team.

Re. Website

The Centre will soon launch its website. Its release will be announced on Twitter and Facebook in the near future. Look out for that.The World Today

As with colleagues in Australia and around the world, the Centre has had to adjust to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and the circumstances of working in a virtual environment.

We have had to postpone many key activities – lectures, collaborative workshops, conference presentations, field trips and much else. We are all working from home, and are readjusting our schedule for a much changed research environment.

The team is continuing with projects, activities and initiatives as much as possible, and moving to online environments.

We will keep you posted about some new initiatives soon. And we do hope you can join us.

-

CANCELLED Discovery, deep history, and other stories for a Greater Australia

THIS EVENT IS CANCELLED DUE TO THE CURRENT COVID-19 OUTBREAK.

This lecture is free and open to the public.

With the 250th anniversary of Lieutenant James Cook’s arrival at Botany Bay in April 1770, we are reminded of how this moment of European Discovery is still widely seen to mark the beginning of historical time in Australia. Is this a fitting origin story for today? And why is there seemingly only one ‘discovery’? Australia’s deep history, its over 60,000 years of Indigenous occupation of the Australian continent, are seen as static, as cultural perhaps, but not quite as historic. This Lecture will explore the legal and conceptual power of both new and old discovery narratives. It will explain what happened when scientists attempted to share the kudos of scientific discovery with Indigenous Australians at Lake Mungo/ Willandra Lakes. It will then turn to consider aspects of Indigenous deep histories of migration and discovery, such as David Unaipon’s story of the arrival of a people who travelled via the ancient continent of Lemuria. In European scientific and theosophical imagining, Lemuria was a fantastical land with land bridges to other continents, and which, according to Rudolf Steiner, was inhabited by a superior race. It appears that Unaipon was melding Indigenous knowledge of the Pleistocene-era continent now better known as Greater Australia or Sahul with contemporary European scientific ideas. In order to become a greater nation, I argue that Australians today need to consider a range of knowledge systems to appreciate the full scale of their continent’s long and dynamic history.

Date and time

Wed 18 Mar 2020, 6PMLocation

Kambri Cinema, Cultural Centre (Building #153), Kambri Precinct, University Avenue, Australian National UniversitySpeaker

Ann McGrath AM is the W.K. Hancock Distinguished Professor in the School of History at the Australian National University, where she is Director of the new Research Centre for Deep History and holds the 2018 ARC Kathleen Fitzpatrick Laureate Fellowship. She is a Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences and the Academy of Humanities. Her publications include Born in the Cattle: Aborigines in Cattle Country (1987) which won the inaugural WK Hancock Prize of the Australian Historical Association, and more recently Illicit Love: Interracial Sex and Marriage in the United States and Australia (2015) which won the NSW Premier’s History Prize. With Mary-Anne Jebb, she co-edited Long History, Deep Time (2015). With Ann Curthoys, she wrote How to Write History That People Want to Read (2009; 2011 ). She has also produced and directed the films Frontier Conversation and Message from Mungo (Ronin Films), has worked in museums and contributed to national enquiries.

W.K. Hancock Chair of History

The WK. Hancock Chair of History is named in honour of Sir William Keith Hancock (1898-1988), director of the Research School of Social Sciences (1957-61) and Professor of History (1957 -65) at the Australian National University. Professor Hancock, a Rhodes Scholar, also held chairs at Adelaide, Birmingham, London and Oxford, was one of four academic advisers who contributed to the foundation of the ANU, and was a leading figure in the establishment of the Australian Dictionary of Biography. Widely regarded as the leading historian of the British Empire and Commonwealth of his time, Professor Hancock made distinguished contributions to Italian, British, South African and Australian History, and he was a pioneering environmental historian.

-

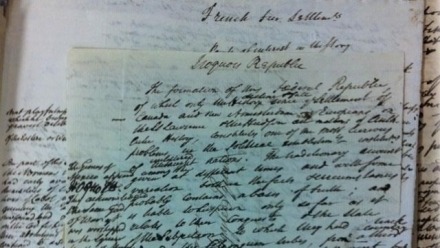

Failed or unfinished? On the fragments of colonial history in Scotland’s Enlightenment

The subject of my paper is an ambiguous figure whose career illustrates the perils, as well as the promise, entailed in the attempt to write a genuinely colonial history of America from within the intellectual heartland of Scotland’s Enlightenment. The Reverend Professor Andrew Brown (1763-1834) attempted what no other Scottish scholar of his generation sought to do. He attempted to write a history of America as a genuinely colonial history – one that placed the colonisation of the First Nations peoples at the centre of his narrative. Brown did not shirk or evade the moral burden of empire, he readily acknowledged the deliberate infliction of suffering on colonised populations. Despite his best intentions however, Brown’s ambitious and morally distinctive project was never brought to completion. Now all that remains of it are several boxes of all but indecipherable literary fragments, from which I will argue, there is still much to be gleaned by intellectual historians of Scotland’s Enlightenment and its entanglements with empire and colonization.

Confronting the remains of Brown’s archive also poses some challenges for intellectual historians. The challenge is not primarily about trying to extract the outlines of a coherent history from disordered, archival fragments (though that is a serious problem in this case). It is a moral question about what was possible within the historiographic frame within which Brown thought, read and wrote. The questions at the heart of deciphering Brown’s mysterious archive are: how could an intellectual in Edinburgh in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century confront the moral burden of empire? Is the fragmentary state of his legacy a testament to his failure, or to his perseverance in questing the impossible?

Date and time

Wed 11 Mar 2020, 4.15PMLocation

McDonald Room, Menzies Library, ANU -

Aspiring future leader Naomi Appleby visit

Naomi Appleby, a project coordination officer in the Future Acts and Heritage Unit at Nyamba Buru Yawuru in Broome, visited us for two weeks in November–December last year. Naomi is a Yawuru and Karajarri woman, and is an emerging curator with a keen interest in the history of Yawuru country in and around Broome. As well as experiencing life on the ANU campus, Ben Silverstein, Postdoctoral Researcher with the ARC Laureate Project, worked with Naomi to explore some of the important holdings held in collections around Canberra.

Naomi and Ben were lucky enough to work with outstanding curators, librarians, and other staff in collections who helped them to access some of the valuable materials that spoke to Yawuru history. They spent an afternoon watching films of Broome, another afternoon exploring the maps and oral history collections at the National Library, and had a couple of visits to AIATSIS to listen to historical recordings of Yawuru language and song. The experience of working collaboratively to research Yawuru history and heritage was memorable for all.

Naomi was also able to meet with staff across the university, including Anne Martin at the Tjabal Centre, researchers working with the ANU Grand Challenges Scheme on Indigenous Health and Wellbeing, and, of course, with staff and postgraduates at the School of History. The RDHP team was delighted to host her visit, and we look forward to future collaborations!

-

Accolades to Professor Julian Thomas, Advisory Committee Member, Dr Henning Trüper, Collaborating Scholar, and Professor Annie Clarke, forthcoming Visitor

Major grants have been awarded to two outstanding scholars associated with Rediscovering the Deep Human Past Program/Research Centre for Deep History.

Professor Julian Thomas, a member of the Centre’s Advisory Committee, received ARC funding to establish and lead the Centre of Excellence for Automated Decision-Making and Society. Based at RMIT, this major new research centre will investigate how rapidly emerging decision-making technologies can be used safely and ethically. It brings together national and international experts from the humanities, and the social and technological sciences. Professor Thomas said the global research project would help ensure machine learning and decision-making technologies were used responsibly, ethically and inclusively. Noting that automated systems are changing our everyday life, he added, “We urgently need a much deeper understanding of the potential risks of the new technologies, and the best strategies for mitigating these risks”.

Dr Henning Trüper has been awarded a European Research Council Consolidator Grant, which provides funding for Henning and four postdoctoral research positions to undertake the project “Archipelagic Imperatives: Shipwreck and Lifesaving in European Societies since 1800”. Henning joined the Laureate team as a visitor early in 2019, leading a workshop on Claude Levi-Strauss and mentoring team members. The Archipelagic Imperatives project is using the historical painting by Danish realist painter, Michael Ancher, as its website image (see below).

In other good news, Annie Clarke, from Sydney University, was promoted to Professor. Annie is shortly joining the Program/Centre as a visitor. Annie is a leading figure both in Australia and internationally in the broad fields of community and contact archaeology, ethnographic collections research and critical heritage studies. Her research profile and interests both connects and adds to the research being undertaken by Ann McGrath and her team. Annie’s record of cross-disciplinary research and public engagement connects directly to the initiatives of the Laureate Program. Her current re-engagement with community-based archaeological research on Groote Eylandt intersects specifically with the research of Laura Rademaker, a post-doctoral fellow with the Program/Centre.

We extend congratulations to Julian, Henning and Annie on these outstanding achievements.

-

CABAH Annual Symposium

From 4–8 November 2019, the ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage (CABAH) held its 3rd Annual Symposium at Monash University. Postdoctoral Research Fellow Dr Mike Jones attended on behalf of the Research Centre for Deep History.

CABAH is a large, multidisciplinary program of work which aims “to tell a culturally inclusive, globally significant human and environmental history of Australia.” Each year project investigators, associates, early-career researchers, postgraduate students, and professional staff from institutions around the country come together to share their work.

Projects span the continent and surrounding regions, with flagship initiatives located in the Northern Gateway to Australia/Sahul, the Top End, the north-eastern Coral Sea, and the South East. Themes include people, climate, landscape, wildlife, time, and models, all with community partnerships and collaboration at the forefront.

There were many interesting sessions throughout the week, starting with an opening workshop titled You Have Excavated It—Now What? which provided tips and techniques for lifting and conserving objects during fieldwork, led by Holly Jones-Amin and Dr Matthew McDowell. CABAH Director, Distinguished Professor Richard ‘Bert’ Roberts, opened the second day with an overview of the centre’s mission, goals, and progress to date.

A series of presentations, ‘pico’ talks, and posters followed on a range of topics. To sample just a few, we heard about migration and the modelling of routes through South East Asia; rock art in Australia’s north; the use of drones and photogrammetry to explore fish traps in the Gulf of Carpentaria; Queensland’s Holocene Indigenous fisheries; explorations of the deep history of Bass Strait; research into fire and vegetation change around Gariwerd; the interaction between people, climate, and water scarcity in relation to megafauna extinction; pollen research; dating techniques; and new research into people’s use of Cloggs Cave in eastern Victoria.

Along with the Research Centre for Deep History, CABAH shows the growing interest in expanding our understanding of the deep past of Australia and its peoples. Thank you to Professor Lynette Russell and the CABAH team for allowing us to attend a fascinating week filled with new insights and connections.

To find out more about CABAH, visit: https://epicaustralia.org.au/