-

Swedish Research Council grant for Bruce Buchan, RDHP/RCDH’s next visitor

The Rediscovering the Deep Human Past Program/Research Centre for Deep History team is very excited about the visit by Bruce Buchan, an intellectual historian, from Griffith University early next year. Bruce’s visit to the School of History was enabled by the generosity of the visiting fellowship scheme at the Research School of Social Sciences.

Bruce and colleague, Linda Andersson Burnett, from Linnaeus University, have recently been awarded funding by the Swedish Research Council to undertaken a new four year project “Collecting Mankind: Prehistory, Race and Instructions for ‘Scientific Travellers’, circa 1750-1850”.

This research project will be the first investigation of the emergence of the concept of race from a hitherto neglected transnational history of instructed scientific travel, collection, and museum displays of peoples deemed “prehistoric”. The project will explain why and how the amorphous Enlightenment concept of race hardened into categories of racial hierarchy at the same time as the notion of prehistory also began to take hold in European scientific thought before 1850.

As Bruce commented on receiving news of the grant, “The timing could not be better”, given next year’s 250th commemoration of James Cook’s colonial legacy in the Pacific. He noted that overnight the British Government has been called the largest receiver of stolen goods in the world and that calls for apologies, reparations and compensation for slavery and colonial atrocities were mounting.

The RDHP/RCDH team congratulate Bruce and Linda on this outstanding achievement and look forward to Bruce’s forthcoming visit.

-

The Research Centre for Deep History launched!

Over 80 people gathered in the The Lotus Hall to participate in the launch of the Research Centre for Deep History. In a warm Welcome to Country, Auntie Matilda House spoke about the value of Indigenous and women’s history. Auntie Matilda also spoke about the important shift in the scale of Australian history that the Research Centre would drive. She could see how it would support younger generations, including her three great grandsons, to know, learn and respect country and the depth of Indigenous history and knowledge.

Vice Chancellor Professor Brian P. Schmidt officially launched the Research Centre, noting its national benefits and the way in which it would shape modern history as well as the histories of the deep human past. “The story of humanity is a shared story”, he noted, “and our narratives and deep histories reflect that”.

Presentations followed by Professor Rae Frances, Dean of the College of Arts and Social Sciences, and Professor Frank Bongiorno, Acting Director of the Research School of Social Sciences, and Head of the School of History.

A statement from Professor Jaky Troy, the Chair of the Advisory Board, was read by one of the Research Centre’s team, Dr Laura Rademaker. Professor Troy applauded the Research Centre, because it would give “Indigenous people worldwide the opportunity to share knowledge, share histories that are documented in our minds, our landscapes, our music, our languages”.

Finally, Professor Asmi Wood, Acting Director of the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, spoke about continuing Indigenous sovereignty. “This always was and always will be Aboriginal land. History can inform those who have come later to be truthful and acknowledge what was here when European colonisers took these lands based on legal fictions”.

A major initiative emerging from the Rediscovering the Deep Human Past Laureate Program: Global Networks, Future Opportunities, the establishment of the Research Centre for Deep History was driven by the passion of its Director, Professor Ann McGrath.

Professor McGrath had always wanted to push history beyond the constraints of conventional post-1770 accounts of Australia’s human history. The emerging field of “deep history” offers the opportunity to reframe the past through engagement with western and Indigenous science and storytelling for up to 65,000 years of settlement. The Research Centre will allow different kinds of historical imagination to operate, which in turn will benefit historians and the academy, including a plan to create an interactive digital ancient memory atlas.

The launch had an outstanding show in the media. The news was covered across media platforms including two national newspapers, a national radio program, a NSW/ACT state-wide radio program, local television, and online. Here are some of them: WIN News, Canberra Times, The Australian, ANU News, and CASS News.

-

Good news for Collaborating Scholar, Tom Murray

Tom Murray, one of RDHP’s Collaborating Scholars, was awarded an ARC Future Fellowship last week. His project aims to change our understanding of Australian pre-colonial isolation by demonstrating Indigenous Australia’s connection to South-East Asian cultural and trading networks. This project, re-enacting and documenting profound and centuries-old relationships between Indigenous Australia and Indonesia, will produce a series of films that will demonstrate this trading connection as a cultural route of World Heritage Status akin to other major trading routes such as the ‘Silk Road’. The project will record a collaborative, cross-cultural, documentary history of Australia’s very first international trading relationship, and produce insights into regional history with significant implications for understanding our present.

Tom excels at presenting his research across different media. He is an academic and media producer based in the Department of Media, Music, Communication and Cultural Studies at Macquarie University. Much of his work has been in collaboration with Australian Indigenous communities. Tom’s documentaries have been selected for the world’s most prestigious film festivals. These works have won awards including the NSW Premier’s History Award and the Australian Directors Guild Award for best feature documentary.

The RDHP Team congratulate Tom on this outstanding achievement and look forward to continuing our ongoing collaborations through the newly launched Research Centre for Deep History.

-

Research ethics with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians seminar: A review by Mike Jones

On Tuesday, 17 September 2019, together with RDHP Team members Ben Silverstein and Julie Rickwood, I attended a seminar focused on Research Ethics with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, co-hosted by the ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods, and the ANU Research Services Division. The seminar focused on the importance of reciprocity and the building of trust—ideas which should form the basis of all research, not only with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

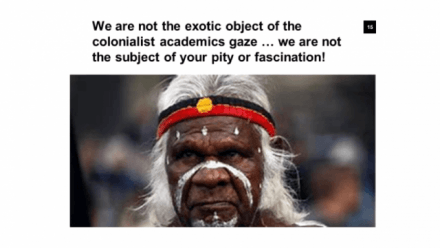

The first speaker was Professor Dennis Foley from the University of Canberra. Foley opened with some key questions: why do people want to research Aboriginal Australia; and what right do white people have to do this research? He continued with a brief tour of useful theoretical frameworks and methodological approaches, including grounded theory, critical theory, critical social theory, Lester-Irabinna Rigney’s ideas on Indigenist research, and the Indigenous standpoint model discussed by Aileen Moreton-Robinson and Martin Nakata, and by Foley in his own work. Of particular interest was the model he presented showing relationships between the physical, human, and sacred worlds and the ideas of Japanangka West, placed in the context of the ocean, land, sky, and stone, water, wind and forest.

Though necessarily cautionary, Foley also encouraged both Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers to continue to engagement with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. He concluded with a call for work that is useful and relevant.

The second presenter was Professor Michael Martin, Chair of ANU’s Human Research Ethics Committee. Martin covered a number of common issues and questions, including reminders that: there is no ‘low risk’ research in this space (though that doesn’t necessarily mean research is ‘high risk’); Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people be involved as partners in the full research process, from design to outputs; and, there are many complexities involved in areas such as consultation, research agreements, use of cultural knowledge, and intellectual property which require careful consideration.

Martin provided a number of useful references and links, from national requirements published by the ARC and NHMRC, to AIATSIS Guidelines (which have been under review and will be updated shortly) and Bevlyne Sithole’s ARPNet Dilly Bag.

Throughout the presentations, and the questions and discussion which followed, there was a focus on Indigenous involvement—as leaders of and partners in research, not just as subjects or participants—providing evidence of a continuing and welcome shift in the perspectives and practices of research. Importantly, the RDHP Team has the benefit of its Advisory Committee, experienced researchers who offer the sage advice necessary to be at the forefront of this shift.

-

Time Immemorial? Dates, History and the Deep Human Past

The Order of Australia Association (OAA)-ACT Branch in partnership with The Australian National University invites you to the 2018 OAA-ANU Lecture presented by Professor Ann McGrath AM.

The concept of time immemorial has poetic resonance, but it also has legal and historical import, dating back to Blackstone’s commentaries on the Laws of England in the eighteenth century. This lecture will discuss its uses by the Cherokee in the United States in the 1830s and in more recent Australian cases. Although Australia’s Indigenous past has often been referred to as ‘timeless’, new archaeological research is delivering a series of hard dates, as well as evidence of inventions and dynamism.

Can new periodizations of the deep past insert themselves into the collective imagination like the anniversaries of British ‘landings’ and ‘discovery’? For the purpose of developing a ‘deep history’ beyond European memory, historians would need to pay attention to Indigenous modes of historical practice and to develop new techniques for understanding Indigenous art, landscape-based memory practices and narratives. More radically, they may need to go beyond dates and to consider other kinds of temporality.

Ann McGrath AM is the Kathleen Fitzpatrick ARC Laureate Fellow and Professor of History at the Australian National University. Her Laureate project is entitled ‘Rediscovering the Deep Human Past: Global Networks, Future Opportunities.’ She is a Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences and the Academy of Humanities. Her most recent book, Illicit Love: Interracial Sex and Marriage in the United States and Australia won the NSW Premiers History Prize, General Category, 2016. She researches and presents history in a range of mediums, including the prize-winning film Message from Mungo (Ronin Films 2014, with Andrew Pike) and in digital works. She co-wrote How to Write History that People Want to Read with Ann Curthoys (2009 2011), and with Mary-Anne Jebb, she co-edited Long History, Deep Past (2015).

Ann was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia in 2007 for service to education, particularly in the fields of indigenous history, as a teacher, researcher and author, and through leadership roles with a range of history-related organisations. She was appointed a Member in the Order in 2017 for significant service to the social sciences as an academic and researcher in the field of indigenous history, and to tertiary education.

Light refreshments will be served following the lecture.

Date and time

Wed 03 Oct 2018, 5.30–6.30PMLocation

Common Room, University House, 1 Balmain Crescent, Australian National University, Acton, ACT 2601 -

Good news for RDHP Advisory Committee Chair and Deputy Chair

Last week was all good news and congratulations on the RDHP Program. RDHP Advisory Committee Chair, Professor Jakelin Troy, was named one of the Financial Review’s ‘100 Women of Influence’. Jaky was recognised for her work on developing the Aboriginal Languages K-10 Syllabus for the Board of Studies NSW, including serving as lead writer of the Framework for Aboriginal Languages and Torres Strait Island Languages. Later this month, Jaky will be speaking at The University of Sydney’s Uluru Statement from the Heart event, Recognition and Renewal, being held at the Old Rum Store, Chippendale on Thursday 26 September.

Professor Lynette Russell, Deputy Chair, was awarded both an ARC Laureate Fellowship and the Kathleen Fitzpatrick Australian Laureate Fellowship. The project will examine 1,000 years of dynamic encounters between Australia’s Indigenous peoples and voyagers from the sea. Together with her role as Deputy Director of CABAH, Lynette’s new project will bring new insights into Australia’s deep history and be of great value to RDHP’s project.

In late July, the Advisory Committee held its inaugural meeting when Jaky and Lynette were appointed to their roles. The morning session focused on establishment arrangements and reporting on the program’s progress from RDHP’s director, Professor Ann McGrath, and postdoctoral researchers Laura Rademaker, Ben Silverstein and Mike Jones. The afternoon engaged all in a conversation on future directions, with guidance and advice from the committee who provided many thoughtful and valuable ideas. Overall, this first meeting of the Advisory Committee proved very fruitful, establishing a firm foundation for the governance and guidance of the RDHP Program and the Research Centre in the future.

-

Patterns of the Deep Past. Interrogating the ‘long term’ in archaeology and history

Date and time

Sat 07 Sep 2019, 10 AMLocation

Bern University, SwitzerlandAnn McGrath to Co-Convene a session at the 25th Annual Meeting of the European Association of Archaeologists

Co-Convened by Shuman Hussain, Ann McGrath and Martin Poor.

Both historians and archaeologists are fundamentally concerned with documenting and explaining long-term change. Yet, there is surprisingly little exchange between the two fields of expertise and both have cultivated different concepts, theories, and visions of the ‘long term’. This situation is understandable in so far as the often-divergent nature of historical and archaeological evidence affords different perspectives and interpretations, but it is also problematic, as each discipline may be diminished by failure to productively engage with each other. In fact, there appears to be a growing transdisciplinary consensus that phenomena of the ‘long term’ should be distinguished from their ‘short term’ counterparts. In historical research, for example, the theme of ‘scale’ has become prominent, with scholars beginning to reflect more deeply upon the internal dynamics and dialectics of varying temporalities of change. In a similar vein, archaeologists have begun to expose diachronic patterns and asymmetries that seem to shape long-term trajectories. In so doing, they are exploring emergent configurations of stability and transformation which cannot be explained only by short-term processes. Key notions such as ‘temporality’, ‘causality’, and ‘historicity’ possibly must be re-considered in this light. What is the specificity of long-term phenomena? What are the mechanisms that drive them? What is the ontological status of patterns of long-term stability and change? What is the relationship between regional and global histories of transformation in a long-term perspective?

The aim of this session is to address some of these questions in the hope of contributing to an integrated, interdisciplinary approach to the ‘long term’. We aspire to bring together scholars who work in different geographic/environmental settings, focus on different types of evidence (e.g. lithic technology, ceramics, other art forms, textual sources), and tackle varying time frames. Our ambition is to discuss phenomena related to the ‘deep past’ and the ‘long term’ in the broadest possible way and to ignite a new dialogue between theoretical concerns and situated case studies in discrete moments of time.

-

Deep History: time, culture and collections

Date and time

Mon 02 Sep 2019, 2PMLocation

422 Iwakura Osagicho, Sakyo Ward, Kyoto, 606-0001, JapanSpeakers

Dr Mike JonesMany aspects of collections relate to time. Identity and significance are often linked to an understanding of dates and historical periods. Some institutions pride themselves on having the oldest, the earliest, or the first. Artefacts exist for a period of time, marked by key events (creation, acquisition, display), with museums often attempting to slow the inevitable forces of entropy and decay through conservation work. Meanwhile, all these physical things we collect and document can only be in one place at a time.

But the concept of time is also complex and culturally specific. Galilean physics (referenced in the explanation for ‘E52 Time-Span’ in the CIDOC-CRM) is premised on linear temporal extents, with a beginning, an end, and a duration. Alternative ways of thinking can be found in Australian Aboriginal knowledge systems, where time is layered and overlapping, the past, present, and future co-existing on and within the landscape. Here, things are neither timeless nor fixed in time; they have temporal depth. Recent scholarship in deep history has started to explore these ideas, developing longer, deeper narratives by looking beyond the constraints of colonial archives to the entanglement of artefacts, stories, places, imagery, and experience. At the same time, digital technology provides new opportunities for opening up the way we manage and represent information about time, creating spaces in which things can co-exist in multiple temporal and conceptual contexts simultaneously.

In this paper the author will explore notions of time as represented in museum documentation. Drawing on Australian collections and recent historical scholarship, the paper will make explicit the culturally-specific limitations inherent in the way we capture dates and time-spans. Placing this work in the broader context of recent research on relationality and the relational museum, the paper argues for a rethinking of collection description in the digital age, opening up time in ways that better represent the cultural and contextual complexities of the things we seek to document.

-

RDHP’s Neil Brougham reviews Sacred Histories Symposium

The Sacred Histories Symposium, held on Friday 23 August, was co-hosted between the Rediscovering the Deep Human Past ARC Laureate Program (ANU) and the Faculty of Arts at Macquarie University; co-convened by Dr Laura Rademaker (ANU) and Associate Professor Clare Monagle (Macquarie). The symposium set as its ambitious aim “to highlight the importance of recognising experiences that subjects experience or know as ‘sacred’ in the historical record”, and in particular to experiment with “dangerous” or “radically cross-cultural histories” in which the sacred might illuminate the “histories of different peoples and places”.

Ultimately, the symposium would not deliver its aim – for it rarely attempted a definition of the sacred, nor its embodiment in practice, and said little that was cogent about the history of (forms of) the sacred as such – but it did deliver something equally provoking and important: how contestations over the sacred – be it sacred ground, sacred buildings, sacred trees, sacred people or gods etc. – was a schematic of colonial encounters and a propaedeutic for historical discourse. In this context, what the symposium actually materialised was not a deeper understanding of the sacred, but rather how the power-relations inherent in competing views of the sacred are manifested in time – and primarily within colonial time – and, importantly, begged the question of the “sacred” right to theorize about “the other” from the position of oneself.

It is important to note that Len Collard and Laura Rademaker were unable to attend; their late (unexpected) withdrawals no doubt had an impact on the proceedings.

But despite not bringing the sacred any closer to comprehension as such (i.e. as a felt or explicitly defined aspect of experience), the symposium presented nuanced and intelligent papers on the contestations of the sacred in time; and the forthright question-and-answer sessions left none in doubt that sacred sensitivities had been breached!

The keynote speaker, Donovan Schaefer, delivered a sermon on the “schisis” (schism) of religion and secularism in late 17th century based on the construction of the Sheldonian Theatre in Oxford, to excise rowdy disputations from the sombre surrounds of the University Church of St Mary the Virgin – a schisis whose foundation was one predominantly of affect: of a variation in emotions pertaining to the sacred, and a desire to keep them separate.

The theme of (schism of) sacred affect would permeate the symposium: Notre Dame’s burning and the multi-million dollar pledges for its immediate reconstruction was compared to the (slated) destruction of the Djab Wurrung trees near Ararat for the construction of a highway, which has gone almost unnoticed (Clare Monagle); the stability of Nyungar virtues in deep time, demonstrated to descend from sacred Nyungar knowledge (Aileen Walsh), formed a stark contrast to the capitalist juggernaut which has destroyed the planet’s ecosystem in mere centuries; while the “encounter of laws” – that of Aboriginal law derived from country and monotheistic law inherent to Christianity – produced a torrid colonial frontier experience of contested sacrality (Joanna Cruickshank), one whose reconciliation Katherine Massam considered possible – at least at a local level – through collaborative liturgical expression of the memory of the death and rebirth of Jesus and the palliative of syncretic religion.

The symposium closed with a lively presentation by Shannon Foster, whose presentation title – the “Rematriation of her story” – pointed directly to the schism it intended to address: the inequity of gender relations, a fight for the female voice which became, ultimately, a fight for the substantive earth (Mother Earth). This was followed by a showing of the short film Devil’s country (Juanita Ruys). The film opened with a white, British ultra-marathon-runner admitting he was perennially afraid of the Australian bush, and closed with a barrage of questions and comments from the symposium audience – particularly its non-Caucasian members – about appropriate engagement with Indigenous people in the production of documentary items (be they writing, video, sound, art, etc.) containing their voices and, by implication, their view of the sacred.

That schism would be the predominant theme in a symposium supposedly about the sacred is curious, but not unexpected: be it based on emotions (affect) or concepts, the experience and expression of the sacred comes out differently for different people and different cultures – which is what gives the sacred its historical trajectory (and, perhaps, its actual sacrality). Syncretism notwithstanding it is hard to fold the forms of the sacred into one another, and it is hard to fold them together into a conception of the sacred in general, or into a history without antinomies. This leaves one wondering whether reconciliation between factions of the sacred is, in fact, possible at all, or if the history of the sacred will not turn necessarily into histories of power relations.

This would be too defeatist (and too Marxist?), however, and is not what the symposium intended. Ultimately, new conceptions of history are required (probably ones that deal with the constitutive aspects of the sacred in experience itself) that escape the regress into a descriptive of power dynamics. In this sense the symposium restated, but did not entirely, meet its aim; but it did demonstrate the attempt was fraught with danger and well worthy of attempt.

But above all one was left with the feeling that many people do care, and actively engage, in the right of others to have their own form of the sacred, and that such forms ought to (and can?) exist contemporaneously. True, we do not yet know how to reconcile in the substantive sense our views of the sacred – in policy, gender relations, decisions over sacred objects and places, in the academic literature and the writing of histories, etc., the ground will remain contested – but that a mixed audience could come together, listen to expertly presented seminars on the histories of the sacred, and pose forthright and highly pertinent questions and objections, is critical. To this end, Laura Rademaker and Claire Monagle are to be commended for conceiving of a novel approach toward history and the sacred, packaging it into a public symposium full of high quality and interpenetrating presentations, and delivering a vibrant and engaging program.

-

Sacred Histories symposium

Date and time

Fri 23 Aug 2019, 9 AM – 4.30 PMLocation

Menzies Library, Australian National UniversitySpeakers

Donovan Schaefer

Laura Rademaker

Clare Monagle

Aileen Walsh

Katharine Massam

Joanna Cruickshank

Louise D’Arcens

Juanita Feros Ruys

Sally Treloyn

Convenors: Laura Rademaker and Clare Monagle.

Hosted by the ARC Laureate Program for the Deep Human Past & ANU College of Arts and Social Sciences

Co-hosted with the Faculty of Arts at Macquarie University & the Macquarie Node of the Centre of excellence for the History of Emotions

Keynote by Prof Donovan Schaefer, author of Religious Affects: Animality, Evolution and Power.

For Australian Indigenous people, knowledge, experiences and connection to what has been called the ‘sacred’ have often underpinned their claims to land, sovereignty and knowledge of the deep past. Experiences of settler-colonialism, therefore, have been not only an invasion of Indigenous land but also an attempt at elimination of Indigenous claims to ‘sacred’ knowledge, often dismissed as ‘myth’ or ‘superstition’. But the project of settler-colonialism was also ground in sacred claims. Colonialists understand their practices, their invasions, and, their erasures, as participation in a form of sacred or salvation history that privileged particular notions of whiteness, civilisation, Christianity and progress. These ideas of the sacred, as a mode to legitimacy, will be the subject of this symposium.

The symposium aims to highlight the importance of recognising experiences that subjects experience or know as ‘sacred’ in the historical record. Historian Minoru Hokari called for historians to experiment with ‘dangerous history’, by which he meant radically cross-cultural histories that engage with the historical practices and lived experiences of people of different cultures, including their experiences and knowledge of the sacred. Settler-colonial states, such as Australia, imbricate a myriad temporalities of sacredness at the same time and in the same place. How can we track these imbrications, and negotiate the relationships between them? An attentiveness to the sacred will enrich not only histories of settler-colonial contexts, but also histories of the so-called ‘old’ world. We are interested in what might be revealed by juxtaposing the ‘sacred’ histories of different peoples and places.

Our interest also obtains to the historical record writ large. Following philosopher’s Charles Taylor’s emphasis on ‘experience’ and the approaches of scholars such as, Donovan Schaefer, Robert Orsi and Alana Harris, we seek to engage with subjective understandings of experiences of the sacred. We are interested in expressions of the sacred as embedded in the domestic, the material and the embodied and how these can inform our histories. This symposium will also explore the practice of writing history through the lenses of materiality, affect and lived spiritual experience. It will bring together scholars from vastly different fields, but with a shared interest in the sacred in history to develop fresh approaches to what is being called ‘post-secular’ history as well as to ‘deep’ history seeking to engage with with Indigenous knowledge of the past, often expressed through the sacred and in ritual.

The day will also include a film screening and discussion of The Devil’s Country.